Historic American Homesteaders You Should Know

Homesteading is more than just a chapter in American history—it’s a testament to resilience, determination, and the pursuit of opportunity. Through the Homestead Act of 1862, ordinary individuals shaped the frontier, laying the groundwork for communities, agriculture, and innovation that transformed the nation. Their stories deserve to be told, not just for their historical significance but for the inspiration they provide.

The Homestead Act of 1862

On May 20, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act into law, offering 160 acres of federal land to anyone willing to settle, cultivate, and improve it over five years. This groundbreaking legislation aimed to encourage westward expansion, providing a tangible opportunity for Americans to own land and build their futures. Immigrants, freed slaves, single women, and other dreamers took up the challenge, contributing to a dynamic reshaping of the country’s demographics and geography.

But this golden opportunity came with significant challenges. The act failed to adequately address the needs of Native Americans displaced from their ancestral lands and presented barriers for African Americans, who often faced discrimination even after the Civil War. Despite its flaws, the Homestead Act stands as a powerful symbol of American ambition and enterprise.

Pioneering Homesteaders

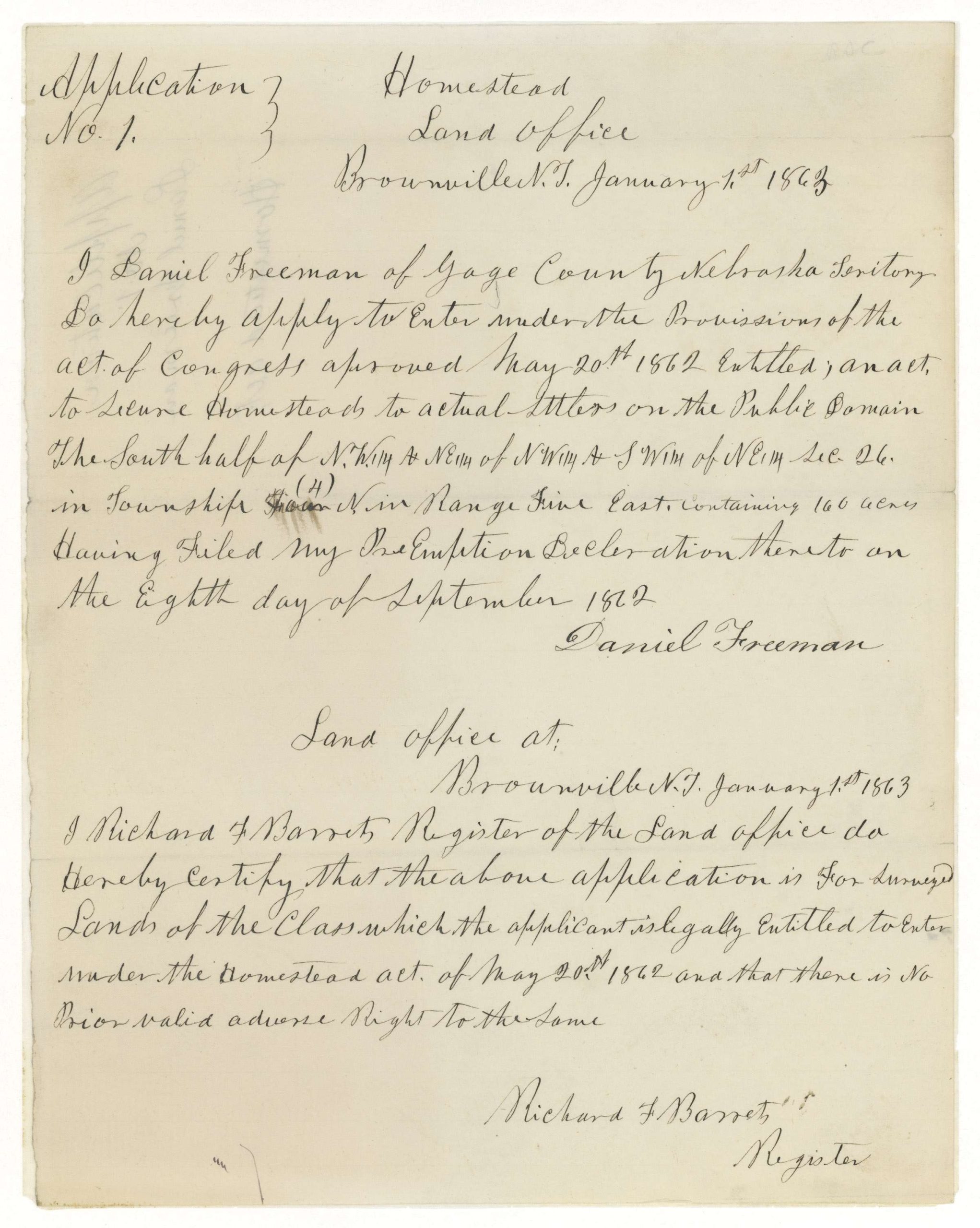

Daniel Freeman: America’s First Homesteader

Daniel Freeman is credited with being the first homesteader in America. According to the National Park Service, “Legend has it that Daniel Freeman filed his claim 10 minutes after midnight at the Land Office in Brownville, NE on January 1, 1863, the first day the Homestead Act went into effect.” Knowing this, isn’t his last name fitting?

Freeman claimed 160 acres in Nebraska, where he built a thriving homestead. He married Agnes Suiter in 1865, and together they had eight children, who expanded the family’s presence on the land. Their property included a log cabin, brick home, barn, orchards, and farming outbuildings. Nearby stood the Freeman School, a one-room schoolhouse that served the community for decades. Today, his homestead is preserved as Homestead National Historical Park, symbolizing the pioneering spirit of America’s first homesteader.

Mary Meyer: A Female Trailblazer

Mary Meyer, Daniel Freeman’s neighbor, holds her own place in history as the first female homesteader in the United States. In 1863, she filed her claim for 160 acres in Nebraska, shortly after the Homestead Act took effect. Widowed before her filing, Meyer chose not to remarry, owning and cultivating her land until 1877.

Meyer’s story highlights the significant role of women in homesteading. Historians estimate that single women accounted for about 25% of homesteaders in Nebraska, taking advantage of the act to secure their own economic and social power. Meyer’s land featured a home, orchards, and livestock—a testament to her determination and independence.

Wilder Ingalls and the "Little House" Legacy

The Wilder Ingalls family became famous thanks to Laura Ingalls Wilder’s beloved "Little House on the Prairie" series. These books, based on real events, recount the family’s experiences as homesteaders in South Dakota. The challenges they faced—harsh winters, crop failures, and relentless labor—were all part of frontier life.

At 18, Laura met Almanzo Wilder, another homesteader, and they married. The couple eventually settled their own homestead in Mansfield, Missouri, in 1894. Today, fans of the "Little House" series can visit the Wilder Homestead and other sites to learn about the real-life inspiration behind these stories.

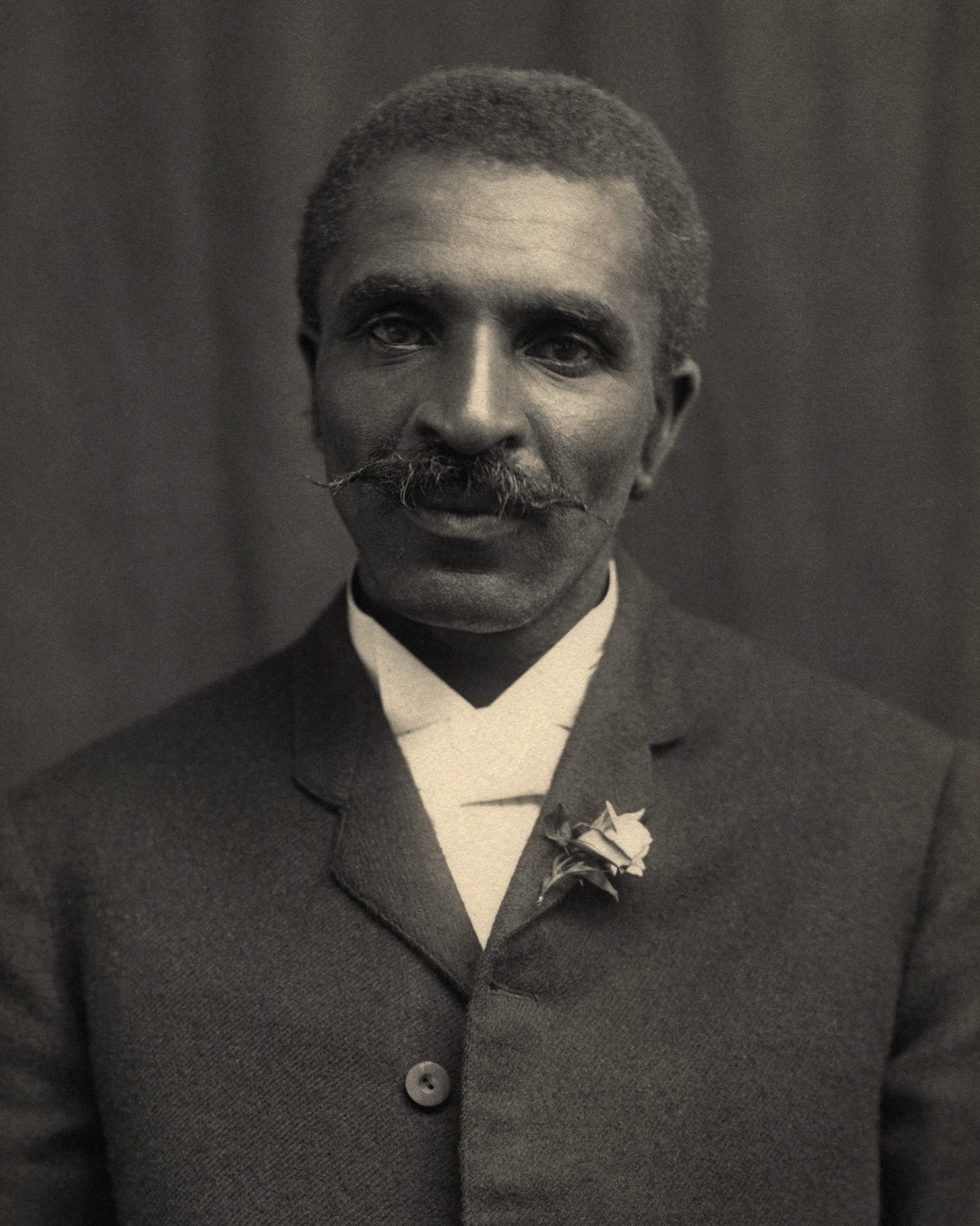

George Washington Carver: Innovator and Homesteader

George Washington Carver’s journey to becoming an agricultural pioneer began with homesteading. Born into slavery, Carver filed a claim for a quarter section of land near Beeler, Kansas, in the late 1800s. Though he did not complete the requirements to secure the patent, his time on the frontier influenced his innovative spirit.

Carver developed over 300 uses for peanuts, 108 applications for sweet potatoes, and 75 products derived from pecans. His contributions to sustainable farming practices helped transform agriculture, particularly for impoverished farmers in the South. While his sod house has disappeared, Carver’s legacy endures as a symbol of resilience and creativity.

Ken Deardorff: America’s Last Homesteader

Ken Deardorff holds the distinction of being America’s last official homesteader. A Vietnam veteran, he filed a claim in 1979 for 50 acres along Alaska’s remote Stony River. Deardorff faced immense challenges, living in a tent while building a cabin and navigating the wilderness with chartered planes and boats.

To sustain his homestead, he opened a small general store, hunted, and trapped furs. Although the Homestead Act was repealed in 1976, Deardorff’s claim was grandfathered in, and he received his patent in 1988. His story closes the book on over a century of homesteading in the United States.

Elinore Pruitt Stewart: Advocate for Female Homesteaders

Elinore Pruitt Stewart’s letters, compiled in Letters of a Woman Homesteader, offer a vivid account of life on the frontier. A widow who claimed land in Wyoming in 1909, Stewart’s writings celebrate the independence and opportunities that homesteading offered women. Her story inspired many to follow in her footsteps and remains a testament to the power of perseverance.

Oscar Micheaux: The Homesteader Filmmaker

Oscar Micheaux’s journey from South Dakota homesteader to groundbreaking filmmaker illustrates the diverse paths homesteaders took. His novel, The Homesteader, drew from his life experiences and tackled themes of race and opportunity on the frontier. Micheaux later became one of the first African American filmmakers, using his platform to challenge stereotypes and inspire change.

Susanna Salter and Family: Community Leaders

Susanna Salter’s family homesteaded in Kansas, where she grew up surrounded by the values of hard work and community. In 1887, Salter became the first woman elected mayor in the United States. Her story shows how homesteading nurtured leadership and civic engagement, leaving a lasting impact beyond the land itself.

Diverse Homesteaders

Homesteading drew people from diverse backgrounds, each bringing valuable skills and traditions. Immigrants from Germany, Scandinavia, and Ireland contributed significantly to frontier development. German settlers excelled in advanced farming methods and durable construction, while Scandinavian settlers brought expertise in dairying and cold-weather farming.

African Americans, including freed slaves, sought opportunities through homesteading after the Civil War. Despite systemic racism and significant barriers, some established thriving communities. Notable among them was Nicodemus, Kansas, a settlement built by African American homesteaders striving for self-reliance and freedom.

Native Americans suffered the most from the Homestead Act, as the influx of settlers led to widespread displacement and the loss of ancestral lands. While the act symbolized opportunity for some, it also deepened injustices against Native tribes, disrupting their cultures and livelihoods.

These stories underscore the varied experiences of homesteaders, revealing both the opportunities and the costs of America’s westward expansion.

Challenges of Frontier Homesteading

Homesteading demanded immense effort and resilience. Settlers faced harsh weather, isolation, and scarce resources. Constructing homes, clearing land, and growing crops required relentless labor, often without immediate rewards. Natural disasters like droughts and blizzards could destroy years of progress, forcing many settlers to abandon their claims.

These hardships forged a culture of perseverance and ingenuity, as settlers adapted to overcome the difficulties of frontier life. Their legacy remains a cornerstone of American history, reflecting the tenacity required to thrive in challenging conditions.

Homesteading During the Great Depression

During the Great Depression, homesteading saw a revival as families sought self-sufficiency to survive economic hardships. Urban residents turned vacant lots into community gardens, while rural families leaned on homesteading traditions to weather the crisis. Nicodemus, Kansas, and other communities became examples of resilience during this era.

The Dust Bowl, caused by unsustainable farming practices, devastated many homesteads in the Great Plains, underscoring the importance of environmental stewardship. This period reinforced the enduring value of resourcefulness and the need for sustainable agricultural practices.

The Back-to-the-Land Movement

The 1960s and 70s saw a renewed interest in homesteading, driven by a desire for sustainable living. Influential figures like Helen and Scott Nearing advocated for self-reliance and harmony with nature. This movement emphasized organic farming, renewable energy, and simple living as alternatives to industrialized society.

The ideals of this movement laid the foundation for modern environmentalism and continue to inspire individuals seeking a lifestyle centered on sustainability and independence.

Modern Homesteading in the 21st Century

Homesteading today adapts to modern challenges, blending traditional practices with new technologies. In rural, suburban, and even urban settings, people grow their own food, raise livestock, and utilize renewable energy to reduce dependence on external systems. Online communities and social media have made knowledge-sharing easier, fostering a global network of modern homesteaders.

The COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the importance of self-sufficiency, prompting many to embrace homesteading practices as a way to navigate uncertainty. Modern homesteaders continue to champion sustainability and resilience, ensuring that these principles remain relevant in an ever-changing world.

Legacy of Homesteading

Homesteading has left a lasting impact on America’s land and culture. Figures like Daniel Freeman, Mary Meyer, and Oscar Micheaux exemplify the determination and vision that built a nation. Their stories, alongside the countless unnamed pioneers, reflect the sacrifices and triumphs of those who sought better lives through homesteading.

Preserving historical homestead sites and sharing these narratives helps ensure future generations understand this critical era. Whether exploring Homestead National Historical Park or practicing modern self-sufficiency, the spirit of homesteading endures as a reminder of human resilience and innovation.